Following the inauguration of Donald Trump as the country’s 47th President, commentators of all stripes are scrambling to interpret the changes reshaping the United States. Yet, many Americans seem ill-equipped to grasp the nature of what is happening. The very structure of our government and the functionality of our democracy are undergoing seismic shifts.

On the right, this is hailed as a “second American Revolution,” a return to a vague and largely mythological golden age. On the left, the reaction has been fear and outrage by observers who believe they are witnessing the advent of American fascism.

But stepping back and placing these developments within a global context reveals a different story. We are witnessing the regression of American democracy to the global norm after decades of exceptionalism. For Americans accustomed to post-war stability and institutional strength, the realities of recent politics—and the peculiarities of Trumpism—may seem unprecedented. But to those familiar with developing democracies, they appear strikingly familiar.

As someone whose academic credentials were forged studying democracy in Latin America, I have a uniquely advantageous position for understanding the politics of modern America that I hope to share with the DS readers in the days and years ahead. While Americans often compare their political systems to those of Western Europe or other developed nations, the new American political reality has far more in common with countries like Mexico, India, or Brazil. Though many around us may fear they are living in 1930s Germany, they would find themselves better equipped for the future by studying 1940s Argentina.

Deexceptionalization

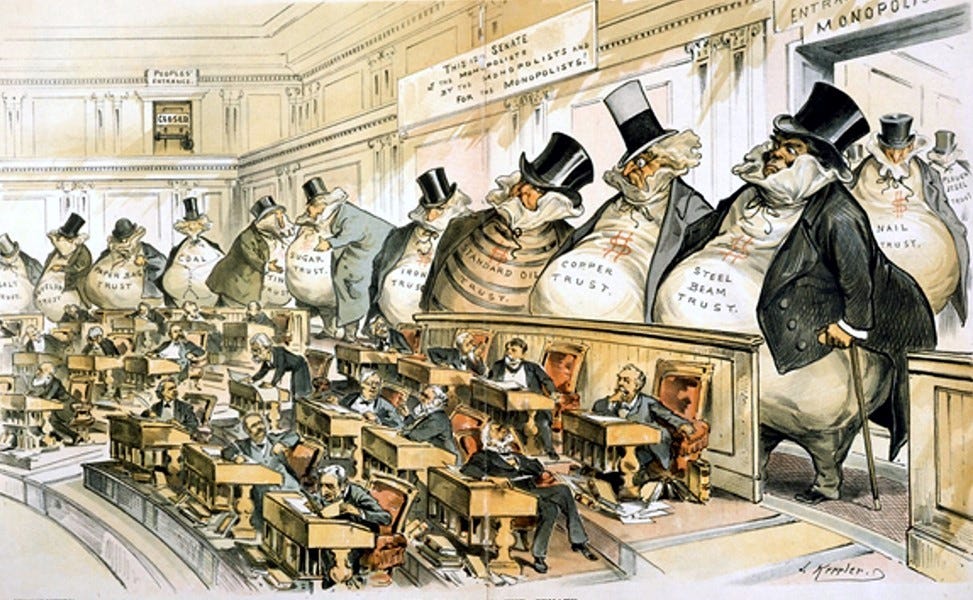

As the second Trump Administration begins, the nature of government and democracy in America is radically different than it was when the first one came to power. Both the outgoing and incoming Presidents have brazenly used executive power to meddle with the Constitution and shield supporters from justice. The new administration openly boasts of plans to convert the government into a machine staffed by loyalists who will carry out the executive’s agenda without question. Populist politicians with cults of personality dominate on the right and left. Meanwhile, billionaires and moguls have funneled staggering sums into the President’s coffers as the private sector scrambles to prove its subservience to the head of state and buy some influence. Some of these figures have become so powerful that they now function as unofficial extensions of the government, wielding immense sway over policy. Politics has devolved into a zero-sum game of rewarding winners and punishing losers.

To many Americans, this state of affairs is shocking. Yet, if you told a Brazilian that their President was allowing a friendly billionaire to directly meddle in the affairs of government or a Mexican that their President was shielding allies from legal consequences, they would not be shocked. Angered, frustrated, or dismayed, perhaps—but not shocked. The new conditions of American politics are routine features of governance in developing democracies.

While these developing democracies are flawed—sometimes deeply so—they are not illegitimate. Brazil, for example, has conducted uninterrupted free and fair elections since 1989, and Mexico since 2000. Such countries have struggled to overcome deep legacies of inequality, colonization, and political instability, with competitive politics only achieving legitimacy in recent decades. The same set of circumstances is true for many countries across Latin America, Africa, Asia, and Eastern Europe. While many of these countries are generally improving the quality of their democratic governance over time, the United States is regressing in the opposite direction.

Exceptional Democracy

Democracy as it exists today in much of Western Europe and countries like Australia and Canada is truly exceptional in that it is rare. Notably, democracy in these countries is to a degree the result of attempts by those countries to imitate the United States’ post-war exceptionalism.

That is not to say democracy anywhere is perfect; it isn’t. But in these countries, the rule of law is strong, democratic norms are broadly respected and induce acceptable political behavior from most actors, political violence is rare, political participation is accessible, political institutions are legitimate and neutral, and standards of ethical political behavior and accountability are high and enforced.

Today, America’s democracy is beginning to bear a closer resemblance to countries such as Brazil or India than to Canada or the United Kingdom.

How America Became Exceptional

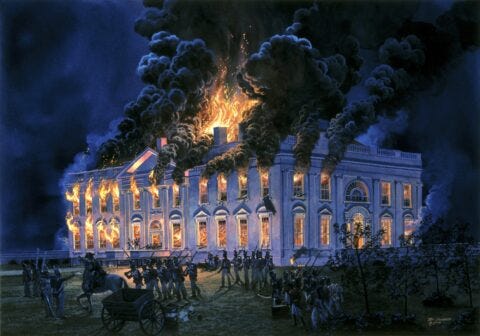

The United States doesn’t just resemble the developing democracies of today; it also resembles its former self. The exceptionalism of late twentieth and early twenty-first century America was the result of deliberate progress. Only after the Civil War amendments did the US come to truly resemble a democracy. The feats of the progressive era in the early twentieth century served to legitimize our institutions and banish widespread corruption. The liberalism of World War II and the hard-won freedoms of the civil rights and women’s liberation movements served to complete the process and make the United States a truly exceptional democracy for all of its citizens.

If you could travel back to the United States of the late 19th century, you would find a deeply flawed country. Corruption was rampant, elections were often fraudulent, scandals were common, and government positions were doled out as political favors. The nation was marked by stark inequality and the direct control of wealthy elites over politicians and public policy.

Why This Matters

The people of Mexico and Brazil don’t appear to be living in a fascist nightmare so why should we care? It’s true, they are not. Elections in developing democracies are mostly free and fair, and the results are usually enforced. People live normal lives and enjoy access to basic freedoms.

Nevertheless, the degradation of our political institutions carries profound and far-reaching consequences. When political loyalty becomes the primary qualification for government positions, the bureaucracy quickly devolves into a bastion of entitled incompetence. This decline renders government increasingly inefficient, biased, and unresponsive to the needs of its citizens. Public services, instead of being accessible and effective, become obstructed by layers of corruption and mismanagement.

As government departments transform into tools for rewarding allies and punishing adversaries, they lose sight of their true purpose: serving the public good. Justice becomes uneven and selective, allowing bad actors with good connections to evade accountability. Politicians, emboldened by the hope that their allies will shield them after the next election, feel free to violate the law without fear of consequences.

Economic growth and innovation suffer as public institutions prioritize favoritism over fairness, rewarding allies at the expense of broader prosperity. Public policy ceases to reflect the public interest or coherent ideology, instead devolving into a stage for petty feuds among elites.

Ultimately, the benefits of a developed and exceptional democracy—often invisible and taken for granted—are lost. These benefits, from reliable public services to the equitable rule of law, will only be fully appreciated when they are gone.

For the United States, the stakes are even higher. As the world’s most powerful democracy, America’s deexceptionalization carries global ramifications. A weakened America becomes an unreliable ally and a destabilizing force in international politics. Its immense military and economic power, wielded arbitrarily, risks chaos on a global scale. That same power will also quickly degrade as the institutions that sustain it rot.

The end of American exceptionalism will have many serious consequences. The causes of this change are complex and difficult to identify in the moment. However, if we want to understand our new political reality and perhaps even chart a productive path forward, then we need to gain a better understanding of the larger changes taking place.

You have left out an important point. The vast majority of the governments of Europe, Japan (which you left out) and those of Canada, Australia and New Zealand, are constitutional monarchies. This means that the very top of the government is very stable, and the voted-in governments need to consult with and report to the monarch regularly. So they can't get away with any of the crap that Donald Trump has just pulled on the citizens of the United States of America. Brexit was a notable departure from the UK's stable government, but it was sold as "independence" from the EU. It has not worked well at all so far, and may continue to decline.

In the meantime, Canada has just pulled all American beers, wines and spirits from 9 of 13 of its provinces and territories, in recognition that the current American government is the most unreliable since the early 1900s.

Well said. I find it disheartening to think that a strong rule of law and respected democratic norms are exceptional rather than the expectation, and truly heartbreaking that this is the country that a clear plurality of us voted for. Again. Sigh.